News

In May 2014 Rebelact will organise a serie of info nights about the present situation in Egypt. Maro, a female Egyptian activist and rebel clown, will give lectures on the recent developments... More

Get Involved

Extra Info

How to prank, play and subvert the system

introducing: the barratt* homes of creativity

* Barratt is a British construction company famous for building millions of houses that look the same all over the islands.

It didn’t take long. By the time Gap’s broken windows had been replaced, advertising types had appropriated the images of anti-WTO protesters smashing glass in the Battle of Seattle, 1999. Diesel swiftly launched its protest chic range, whilst Boxfresh splashed Zapatista leader Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos on T-shirts for £25 a pop. The revolution will be commercialised. Che Guevara T-Shirt anyone?

Images and stories are the way most people will encounter this movement of resistance and creation. One placard that got plenty of media coverage at the biggest 2003 anti-war march in London, was ‘Make Tea Not War’, a placard, it turned out, that was made by an advertising agency. The question is: whose propaganda wins? The black clad unwashed or the Diesel model dressed up to look like they give a shit? Whose side of the story is being told? What effect do charity celebrities such as Bob Geldof and Bono have on radical agendas, and on the way our stories, desires, rage and alternatives are presented?

This movement can and does create powerful images and stories that are vital tools for radical change. When we think about creativity we don’t mean paint and canvas, bright costumes or painting your face. And by images we don’t just mean photographs. What we feel is important is what our stories do and how they are framed. Is the story moving? Is the experience aesthetically pleasing? This may seem a trivial question as global melt approaches ever faster. But, these days the battles happens more in the mental environment of advertising space and public relations trickery than in the streets. On the street activists can score well, but on the other front we are unprepared and losing. Yet crafted new forms of resistance are engaging people and interrupting the system with unpredictable tactics that can’t always be shut down quickly. This approach to an action or event is key in the battle of the story and image, and to the ways in which our actions and beliefs are understood by the people we encounter.

We started to make activist art after hearing stories of a particular, exciting performance. A group known as Fanclub went out shopping. They bought things and then returned them repeatedly, over and over, monopolising the queue, holding shops to ransom with their own logic. Intrigued, we began looking around and discovered other similar groups and actions, such as the Surveillance Camera Players who play in front of CCTV and Whirl-Mart Ritual Resistance, who block the isles of supermarkets, going round and round. The stories of these groups, seeing their rebellious images, which were as seductive as any advert, revealed to us a world of possibilities for cross-pollination of politics and art forms.

For us, the most difficult thing was finding the confidence to try something new. Our friends told us to ‘Just Do It,©’, follow Nike, it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t work the first time. So, on Buy Nothing Day 2002, we organised a party in the Virgin Megastore in the shopping mecca of Camden Town, London, under the name CCCP (Camden Corporate Crackdown Party). As we had feared it turned out to be a crap action. Only three people turned up, not much of a party. But we had tried and this spurred us on to organise the next Whirl-Mart Ritual Resistance actions, which we started in the UK in 2002. We haven’t stopped since.

We share four stories to inspire and motivate. The first story we experienced first-hand, the second we were involved in creating, and the last two we watched from afar with great interest and excitement. We don’t believe we can tell you ‘how to’ subvert the system. We are working on the assumption that the stories we tell could trigger something in your imagination.

Story 1: shop lifting with the church of stop shopping

The Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping are a theatre troupe-cum-direct action affinity group who have focused their actions mainly on Starbucks and Disney, companies with terrible environmental and labour records. Their actions are best described as part space hijacking and part church service. They regularly take over a Starbucks cafe or Disney store with hymns, sermons and exorcisms. We have always been big fans of their ‘Church’. What has inspired us when we hear of their latest adventures (aside from the original idea of having a church against consumption, a 30 strong stop shopping gospel choir and Billy having a restraining order fromevery Starbucks in the USA) is that they keep what they do fresh and unexpected, constantly pushing in new directions. One example was on Boxing Day, 2005 when they hijacked the Christmas parade at Disney Land, Florida. Whilst innovative, the second great thing is their ability to not stop. Most likely we would have burned out by now or changed our angle. But, resembling a radical steamroller, the Church ofStop Shopping is persistent. They aren’t perfect but they are radical both in theirpolitics and their form.

What we’d like to share with you isn’t Disney Land hijacks or Church services to thousands. It is something a little smaller. It was after the G8 summit in Scotland in 2005. The Church were in town. We talked about how the G8 had been, about Geldof and Bono hijacking the agenda, and the 7 July bombings in London before we got around to the topic of visiting a few Starbucks the next day. As we havementioned, Billy is now banned from every Starbucks in the USA after allegedly‘sexually assaulting a till register’, (he was actually exorcising it). They suggestvarious performance options before mentioning an action called Shop Lifting, at whichour ears pricked up. Turns out to be shop lifting, the act of lifting the shop, rather than shoplifting, the act of liberating products. As they explained the plan, we felt that excited tingle and contacted everyone we could think of. We needed at least ten people to carry it off, and we were sceptical.

However, on the morning of the action there was a good crowd: clowns, environmentalists, squatters, academics, experienced space hijackers and some people who had just found out and come along. We started off by sharing our experiences of Starbucks, whether as activist, consumer or neither. It was a very simple exercise but quickly forged a sense of the group, what experiences and expectations people had, and how far people were willing to push things.

Starbucks is designed like an Ikea display. The coffee isn’t the only exploitativeproduct inside; everything from the door handles to the tables and chairs are equally unsustainable. Tracing the origins of products is hard, if not impossible. Yet each object has a story, a point of origin from which we can trace a clear form; a chair was once a tree, a napkin also, a plastic bag was once oil deep in a well. Our action focused on these distant origins, tracing these histories and making them seen, heardand spoken. We did this at the journey’s current end, a Starbucks on New Oxford Street, one of the biggest outlets in London.

At intervals the group enters Starbucks and selects an object they would like to trace. Placing ourselves in the middle of a group of tables, we drag a free chair into the middle of the space and begin. Others are standing in front of the counter, some by the bins, one in front of the door blocking the entrance. There are as many of us as there are customers. We begin quietly, taking our time, following every point of the object’s journey; from the van it arrived in, the warehouse-lorry-boat-lorry-warehouse-lorry, and so on, lifting it every time. The chair that we are lifting is at waist height and we are only on the boat, the chair is nearly above our heads, and we still have a way to go before becoming a tree. Already a few customers have walked out, a lot have walked past, some are ignoring us, others are watching with great interest. Each person, and each history, is getting louder and louder until the music can’t drown us out and this space isn’t a third place anymore; it is made up of trees, drops of oil in a well and coffee beans. Reverend Billy storms in, blond quiff almost two steps ahead: ‘Brothers and Sisters of Starbucks. ..’, he begins his now well-rehearsed sermon about the evils of transnational coffee hell, explaining how on this day we have imagined a new beginning for the objects in this Starbucks. He goes on ... this is a chance for the sinners (shoppers) to move on from the shiny veneer of bullshit, the third place, just off third way. For this moment, the space is ours, everyone has stopped what they are doing, time itself has slowed down. The whole of New Oxford Street seems to know that something different is happening, that the boredom of fashion and fad is momentarily over and that a group of people has found a new religion, the Church of Stop Shopping. The non-shoppers put back the objects where they got them and calmly leave the store. Looking back over our shoulder, the store seems deserted.

We move on to the next Starbucks, conveniently less than 15 metres away, and repeat the action. This time the police are called and arrive very promptly, only to stand and watch, paralysed by a lack of understanding or a fear of being made to look more stupider than we do. Twenty people holding chairs, cups and coffee above their heads, screaming ‘I am now a tree again!’. We disappear into the crowds of people who have gathered outside before regrouping a few blocks away and dispersing to share stories for the rest of the afternoon.

We’ve seen Billy do much pushier things. However, seen as part of a body of work that the Church has undertaken for years, the enormous effect that this group has had becomes clear, and all from having an idea and running with it. By keeping the work fresh and accessible Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping are responsible for a popular alternative that has spread to groups of people who may have never encountered this type of politics in this way before. It’s also possible that it has had an impact on the store itself.

Story 2: the church of the immaculate consumption –praying to products

The Church of Stop Shopping tries to raise awareness about the stupidity of mindless consumerism. An offshoot, the Church of the Immaculate Consumption encourages believers to worship the product rather than buy it. As most people in late capitalist societies understand, consumerism is no longer about getting what you need tosurvive but about reaching godliness, personal fulfilment, through the purchaseof lifestyle. Most people in these societies also understand the iconography of the Christian religion, believers or not. The Church of the Immaculate Consumptionin large cathedrals of consumption (otherwise known as shopping centres) started as small groups quietly getting down on their knees and asking for salvation andfulfilment from the product. Two years later, the Church was holding some of the biggest stores in the UK to ransom with their own logic.

In early 2003, a group gathered around some frozen chickens and prayed, ‘Asda, thank you for these lovely, lovely, fresh, white chickens at cheap, cheap prices’. About ten people saw it first-hand. It was pretty low-grade on the civil disobedience scale but it spread as a story and a short video.

Later we repeated the action in the flagship House of Fraser store, Glasgow and Brent Cross Shopping Centre, London. However it didn’t really take off as a mass effective action until the following year during the 2004 Autonomous Spaces sessions at the European Social Forum in London, as part of the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination’s (Lab of II) programme of events. By this point we’d organised a few more events and were more confident. The target was the Selfridges store, the jewel in Oxford Street’s crown. With around fifty people taking part the action was transformed into an effective way (albeit temporary) to stop people shopping. Working in small groups of three to five, worshippers easily entered the store undetected (despite a number of riot vans and plain-clothed police trying to prevent the acts of worship). Devotees positioned themselves throughout the departments, some in quiet corners, some leaning over balconies so that people on other floors could see them. It was peak time on a Saturday; the shop was a mass of shoppers. We were lucky enough to locate ourselves on a balcony by the main escalators, looking down over the whole central section of the store. With a booming voice we were taken and filled with the spirit of Selfridges, until we were picked up from behind by a large and somewhat bemused security guard.

Groups prayed in their own way, some loudly, some not. After being removed by security staff, groups were able to re-enter through different entrances and continue their prayers. The store was only left with one option, to stop letting everyone in as they couldn’t possibly determine who was a shopper and who was part of the congregation. Rumours vary but some say it was an hour before the doors reopened.

However this wasn’t enough for the Church members. The next level was to repeat the success of the Selfridges action weekly. In the nine cities we visited on the Lab of II tour before the 2005 G8 summit in Scotland, we always headed down to the local multinational cathedral to worship. In this way we could hit the chain in a sustained campaign. Each action was unique, some more successful than others. But each congregation was able to not only hold these spaces to ransom but also to share skills, support each other, and find a point where they were comfortable performing and push themselves from there.

Story 3: nikeground – guerrilla marketing or collective hallucination?

Picture This: Rethinking Space. Having the chance to redesign the city where you live, waking up in the morning and changing the names of streets and squares, to imagine bizarre monuments and then the next day see them become real; it’s the dream of every citizen, it’s Nike Ground! This revolutionary project is transforming and updating your urban space. Nike is introducing its legendary brand into squares, streets, parks and boulevards: Nikesquare, Nikestreet, Piazzanike, Plazanike or Nikestrasse will appear in major capitals over the coming years. (www.nikeground.com)

Picture this: The square and piazzas of major cities, public spaces famous for their monuments, mass demonstrations and tourist hot spots, often with historic names – Trafalgar Square after the battle of Trafalgar, St Anna’s Square after St Anna, Union Square after the famous union marches – these places are steeped in history and collective memory, not just for local people but also globally through images and footage. However, with increasing privatisation of public space should place names not begin to reflect the importance of the corporation? Should we not consider a programme of renaming? Starbucks Square, for example, or McDonald’s Passage? The Nike Corporation, who has always been at the cutting edge of marketing, has already begun this vandalism of our physical and mental space. Vienna, Austria, was the scene of a battle between the local Viennese and Nike’s public relations machine.

Nike, without any consultation of the public, announced that the historic square, Karlsplatz, right in the heart of historic Vienna, was to be renamed Nikeplatz. Nike’s famous ‘Swoosh’ logo would become a giant monument to the corporation and this historic occasion. To mark the event, Nike would open an exhibition centre in Karlsplatz promoting the virtues of having a big name brand as the focus of the city centre. A launch event invited locals to come and learn about Nike’s plans, with freebies and Nike beauties extolling the brand’s virtues. A new trainer was even launched to commemorate the rebranding of the square. The press were notified and, of course, flocked to cover the story.

This would have been an activist nightmare had it been real. It was actually a brilliant prank pulled by the Italian duo known as 0100101110101101. The group had secured permission from the Viennese authorities to install their exhibition by the roadside in Karlsplatz, and the towering Nike ‘Info Box’ looked 100 per cent authentic. Combined with a website, www.nikeground.com, and a few slick press releases, the group had secured an outpouring of hate, shock, disdain and maybe even love, towards Nike for suggesting such an idea.

After a few months the press exposed the Nikeground campaign as a stunt. But, as any public relations person will testify, the damage had already been done. In the minds of Vienna’s consumers Nike had attained a negative status, the brand has been damaged and maybe even lost some of its devotees. Nike’s PR people pulled out all the stops to deny, what was for all intents and purposes, their own propaganda. Resorting to legal action against the pranksters was their only option for rebuke but they eventually dropped the case. One can only wonder that they feared ending up in a PR disaster to rival McLibel. In that now infamous legal battle between two UK activists and McDonalds, the fast food giant exposed its own darkest secrets in an attempt to silence protesters.

The high level of press coverage was what made the prank a success, yet all the pranksters had done was taken the identity and logic of Nike and then pushed it to its next step. Through this 0100101110101101 had revealed the true, hideous nature of corporate globalisation.

Story 4: dow chemicals correction

On 2 December 1984 a chemical leak from a Union Carbide factory released 27 tons of methyl isocyanate gas throughout the city of Bhopal, India. Since that night, it has killed 20,000 people and a further 120,000 people have suffered serious illness, blindness and reproduction problems as a direct result. Despite a sustained campaign by the people of Bhopal to demand a clean up and calls by the Indian government to extradite Warren Anderson, then Chief Executive, on multiple homicide charges, nothing has been done by the company to care for those who were affected. Although Union Carbide, now Dow Chemicals, had let safety at the plant go out the window, to this day they have done nothing to clean up or pay any compensation and US law enforcement has done nothing to turn Warren Anderson over to the Indian authorities.

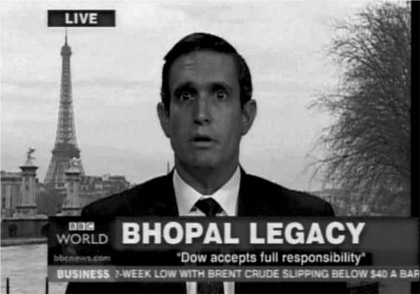

In November of 2004, almost 20 years after the accident, a representative of Dow Chemicals finally got around to apologising on BBC World News. Jude Finisterra said sorry for doing nothing for so long and announced that Dow would pay $12 billion compensation to the victims and remediation of the site and waters of Bhopal, the exact amount that Dow had paid for buying Union Carbide. They also stated that they would push for the extradition of Warren Anderson to India, where he had fled following his arrest 20 years ago. Within minutes, the news of Dow’s policy shift became a major news story. On the German stock exchange Dow Chemicals’ value plummeted, losing the company $2 billion.

Acceptable risk

Six months earlier another Dow representative, Erastus Hamm, had spoken at a banking conference in London. During his presentation he spoke about a new Dow industry standard known as ‘Acceptable Risk’. This is a statistical equation to determine how many deaths are acceptable in the pursuit of large profits. It was designed to help the corporation deal with the skeletons in their closet. Mr Hamm reminded delegates that they could not all assume to be as lucky as IBM, who made a killing from its computer systems sold to the Nazis for counting the Jewish, gay, disabled and other ‘expendable’ people into the death camps. The presentation involved the unveiling of a golden skeleton to help describe the idea of financial profit from loss of life. Numerous bankers signed up for a license to use this new method.

As you have probably guessed by now both Acceptable Risk and the apology turned out to be the work of the Yes Men who had impersonated their representatives in the guise of Mr Finisterra and Mr Hamm. Unsurprisingly, Dow Chemicals were not best pleased when it was revealed that a group of pranksters had not only been able to speak on their behalf, but dramatically rocked their share price, and gone on to paint them as a company that doesn’t see any problems in profiting from killing people. The Yes Men shot to stardom when they released a film about their pranks, speaking on behalf of the World Trade Organisation.

The AGM

A year after launching Acceptable Risk and it is time for the Dow Chemicals Annual General Meeting (AGM). What better opportunity than the AGM of shareholders to wrap up a series of stunts? As it turns out the Yes Men aren’t the only activist group planning to attend and security is tight; all journalists have been banned, everyone is searched on the way in and any recording equipment confiscated. The security guards tell the Yes Men that they like their film, which they have been shown to emphasise the potential threat. But because they have one share in the company the guards have to let them in. Determined to have the last laugh they decide to give it a go; after the usual speeches and a few questions Andy (a Yes Man) is introduced as Jude Finisterra, the same name he gave for the BBC interview:

Hello Bill, shareholders. We made an incredible $1.35 billion this quarter. That’s really terrific. But you know, for most of us, that’ll just mean a new set of golf clubs. I for one would forego my golf clubs this year to do something useful instead – like finally cleaning up the Bhopal plant site, or funding the new clinic there. Bill, will you use Dow’s first-quarter profits to finally clean up Bhopal?The question is quickly fielded away, but Mike (another Yes Man) has the next question in the queue:

Great profits. Now I wanna see you use them to go after some of the creeps who are tarnishing Dow’s good name! I’m looking around and most of the questions are from people who don’t like Dow. Let’s do something about that. We need to get aggressive! Of course you can’t exactly broadside a bunch of nuns with a twenty-gun shoot, and you can’t just kick a disabled kid in the head – but at least you could take care of hooligans, like that guy who went on the TV news to announce that Dow was liquidating Union Carbide. That made a serious stock bounce, and I for one was freaked out! I’ll bet a lot of you were! So, Mr Stavropoulos, are you going about that criminal? And if not, why not?And the response? ‘If you can tell us who that guy is. Next question?’

Over the period of a year the Yes Men had managed to present Dow Chemicals in a completely new light across the world’s media, costing the company probably millionsof dollars, and putting Bhopal back on the media agenda in the USA.

Conclusion: we suck

Think about times when someone has tried to explain or promote an idea, ideology or possibility to you. Imagine you are a Buddhist, a black blocanarchist who defends property damage or that you are an eco-terrorist and your uncle is an oil baron. It is quite possible that you were mutually unsympathetic and at the end of the day, remained unconvinced. The moments we remember listening really hard and being sympathetic to what is being said are times of funny stories, sad moments or seductive possibilities. What could be less appealing than beinglectured about what is wrong with your lifestyle? How a message is presented isintegral to its effectiveness. This is not to say that pranks and creative resistance are the only tools. Sometimes a march from A to B can have a much bigger effect; other times it’s as dull as voting. Sometimes a leaflet can cause major ripples, sometimes no one will read it. Sometimes a lock on is the only thing that will work. But either way if we only rely on what is the done thing or what someone else has tried and tested before, then the power of that tool is reduced. It is easy to categorise, dismiss or ignore it. After all, fresh bread tastes better than stale.

The Vacuum Cleaner are an artist activist collective of one based in Glasgow, Scotland. They make live and digital actions, interventions and pranks, and can be found at www.thevacuumcleaner.co.uk.

Published in the book "Do It Yourself. A handbook for changing our world" by Bluto Press and edited by The Trapese Collective in 2007 under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.0 England and Wales License.